The Star and the Eclipse. Remarks on Forgotten Science

(Susan Leigh Foster)[1]

Hide her starry light

(…)

Weeping willow tree

Weeping sympathy

Bent your branches down along the ground and cover me

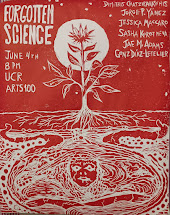

On Wednesday, June 4th, 2025, at 8 p.m., at University of California, campus Riverside Arts100 Dance Studio, it took place the performance Forgotten Science, by Salon’s Performance Collective (Dimitris Chatziparaschis, Jorge P. Yánez, Jessica Maccaro, Jae M. Adams, Sasha Korotneva, and Gonzalo Díaz-Letelier) –a section of Salon Transdisciplinary Collective. Salon Transdisciplinary Collective is an experiment in the composition of bodies and ideas involving graduate students and researchers from different disciplinary areas of the university (arts and humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, formal sciences, medical sciences, and techno-engineering). The group meets weekly to discuss concepts and epistemes that cut across different disciplinary fields, not to reach a common language, but to destabilize the basic conceptualities that the bureaucratic tendencies of university departments tend to fossilize. Salon’s Performance Collective is a transnational (Greece, Ecuador, United States, Russia, Chile) and transdisciplinary (electric and computer engineering, dance and performance, biology and entomology, physics and mathematics, music, philosophy and translation studies) group. I am just one member of the collective, but I would like to share some reflections that also arise from the group’s collective intelligence, although I elaborate on them here from my perspective —from which I see the collective is played out as a singular-plural and anarchic entanglement, not as a community of faith. This reflection is not concerned with art criticism or technical issues related to the mounting of the piece, but rather with the epistemological, ethical, and political dimensions of this performance.[3]

THE AESTHETIC-POLITICAL QUESTION ABOUT THE PIT

There is an old motif, repeatedly taken up from antiquity, about the pit or separation invented by the Greeks between the stage and the audience (theater), and between knowledge and its subject matter (theory).[4] This later theological-Christian separation between the luminous ascending life of the spirit and the dark, cadenced nature of sensible life (the light of the stage, the shadows of the stalls; the light of knowledge, the shadows of its subject matter) would have been translated into its conventional Cartesian secular form in the European and American modernity of the technoscientific representation (subject-object, res cogitans et res extensa), the society of the spectacle, and the sovereign theater—fascism, monumental revolutions, neoliberal “democracy”, etc. Regarding the possibility of a “dance theory”, Susan Leigh Foster writes: “Seems like the whole idea of what a theory is—a hypothesis about what something is and how it works—implies that there is more than one. Aren’t there multiple theories about dance? I mean, hundreds or thousands? / But if the use of the singular is your only objection, can’t you just imagine ‘dance theory’ as the broader category that encompasses all theories? / Maybe. But now you’ve made me see another problem: To call it ‘dance theory’ cordons it off as its own thing, separate from and comparable to ‘dance history’ or ‘dance ethnography.’ And I can’t envision theory as operating at that kind of distance from either method or subject matter. / Wait. You’re saying theory is an integral part of research. / It’s woven into the entire creative-critical process. / Maybe we should call it ‘theorizing’ instead of theory? / Ahhh. The gerund is always so satisfying. But seriously, theorizing can happen throughout the process of conducting research, whether one is making a dance or writing an essay. Theorizing is instigated whenever one asks oneself, ‘What am I doing and why am I doing it?”’.[5] Leigh Foster, similarly to Kember and Zylinska, emphasizes the translative chiasmus between theory and dance-performance as an abolition of the “distance” (or “leveling of the pit”): performative theory / reflexive performance.[6] Leigh Foster: “(…) theory helps you discover new things. As an integral part of investigation, it provides a flexible corpus of assumptions that are always subject to change depending on what you uncover during your ongoing research. I guess I tend to stress the role of theory in research because the emphasis on objectivity in Western culture over the past three centuries has obscured this dialectical back and forth between theory and inquiry that constitutes the research process. / That whole objective/subjective debate? / Exactly. I don’t think there is such a thing as a neutral tool for looking at dance. Every checklist of movement features, every notation system devised, has values and preferences built into it that influence the resulting profile of the dance. (…). Even the ‘neutral’ notions of space and time are culturally specific. Is space some geometric grid into which bodies move? Or is it produced by the interaction between body and environment? Is time metric? Cyclical? Steady or in flux?”[7]

We thus observe a desire to abolish that ontological gap between the dancer and what is danced (or between praxis and theory), and often also between the stage and the audience: the separation between subject and object in the Western modern sense. An abolitionist tendency we often find, since the 20th century, both in “theater” and in “theory”, because both are born from the idea of a gap or a distance between knowing and “what” is known, or between dancing and “what” is danced—in other words, both are outcomes from the passage from ritual to the Greek invention of theater and to the modern spectacle bearing exhibitive value. But a new ontology seems to emerge, according which the medium is the message, and the medium is metamorphic. In some ways, this idea can be linked to this other one: the obsolescence of the “museum” dispositive (artworks as untouchable objects of contemplation and representation; the lifeworld as an untouchable order to be contemplated and followed, but not transformed), in contemporary political aesthetics. And this can also be connected to the concepts of interruption (Bartleby’s “I would prefer not to”) and profanation (as in Agamben’s work, sacred, privatized or institutionalized forms or objects are returned to common use; a child, flouting adult surveillance, playing with sacred objects desacralizes them, reveals the potential to disrupt normative economies of meaning and power).

That interruption and/or profanation has to do with the relationship of each human being with the world (the order of words and things), and particularly with art and politics (the abolition of “distance” as an abolition of the museification of the world). But there is also the relationship between the stage and the audience in art (the abolition of “distance” as an abolition of the theater pit), and this has had a decisive impact on the configuration of Western political imaginaries. But in this direction the problem becomes more complicated when the gap of theatrical distance is leveled: it is another thing to understand this distance as a “critical distance” (in the sense that goes from Kant to phenomenology, among others, as contemplation and exposition of the predominant forces-discourses without subjecting to it) that is broken when the stage imposes itself on the audience or when the audience assaults the stage.[8] In a Benjaminian-Deleuzian entanglement, Willy Thayer, in his 2010 book «Technologies of Critique», describes a series of technologies or ages of “criticism,” each linked to a single metaphor: 1) the organism: discernment of the ei\do~ (intelligible formal aspect) that, as an exceptional unity or e{tero~ ti (“something other”), articulates the pre-understanding and theorization of things and events, giving them unity and meaning, transcending the immanence of the material aggregatum; 2) the theater: exterior point of view with respect to the events, photological and judicative dimension, subject-object correlation); and 3) the singularity: unworking immanence, interruption of the theater of the organic totality; hylomorphism of immanence, undecidability and untranslatability. In his book, Thayer points out the traditional distinction between structure and aggregatum, which operates here as an old ontological assumption rooted in Aristotle: while structure is an organic, living totality, the aggregate is a mere combination of elements, a sum of parts. Structure, then, is more than the sum of its parts: it is a solidary whole whose elements and parts are in a relationship of reciprocal dependence. If we consider the formula “the whole is more than the sum of its parts,” this more (as plus ultra) is neither a mere part nor the sum of its parts, but something else. This “something else” (e{tero~ ti), one and indivisible (the glass can be broken, but not the idea-of-glass as a formal and teleological cause) is what Aristotle thinks of in terms of the “cause of being” (aijtiva tou` ei[naiv), as ontic “presence” and “for the sake of”, as ontological “stability” (oujsiva, substantia): a compound (suvnolon) of “matter” (u{lh) and “form” (morfhv) by virtue of which the form separable by intellectual perception (nou`~) as “formal aspect” (ei\do~) maintains something articulated in its constitutive multiplicity as a unitary organic presence. The old performance of the Greek lovgo~ as “that which gathers and weaves,” whose heritage is expressed in the ideas of centering and transcendent function, general principle of composition, teleology as rigid determinant, soul, etc.[9] Of the three “technologies of critique” (organism, theater, singularity) formalized by Thayer, the first two develop the idea of criticism within the framework or according to the established rational framing (the figure of the art critic who knows the principles and rules of art and taste and who judges according to them); while the third one deploys a critique of the framing itself, questioning its exceptionality (anarchical or postfoundational criticism).

SINGULARITY AND INTERRUPTION OF ORGANIC THEATER

How does the performance Forgotten Science relate epistemologically to this set of ontological problems concerning art and politics? I insist that this corresponds to my view of the piece and the way I worked on it, and that the collective is not a community of faith (so I do not speak as a “representative” or “spokesperson” for the group). I think that, in line with the collective’s discussions on method before and during the process, we brought the third technology into play: singularity and interruption of organic theater. How did we play such an interruption? Let’s see. First, by avoiding the subordination of the action under a plot-and-director dispositive, and also the narratives woven from clear and distinct propositions, as well as diegetics in its classic Aristotelian structure. This involves the destruction of the archaeo-teleological narrative schemes which produce the standardization of perception (automatisms): the dislocation of the schematism of Aristotelian time—the reduction to the One brought about by the dihvghsi~ in the «Poetics». Or, to put it in Walter Benjamin’s words: the problem is the bourgeois conception of language as a “means of communication” of fetishized meanings[10]—by analogy to the trade of commodities, if we understand this in connection with the critique of commodity fetishism in the first book of Marx’s «Das Kapital» read in an aesthetic key—so that the recovery of the communicability of language would involve assuming that experience in its singularity resists its fixation in the ideal element of language and its spatio-temporal schematisms. What are these automatisms and how can performance “break” them? Thayer has observed the first elementary phenomenon: the position of the image under the word to articulate its meaning, “the image is resolved in the unity of the word, of the concept, the endless grammar of the cliché.”[11] This is a critical question, analogously to how John Cage states that, for him, the position of sound under the word, its cliché, was a critical question.

New music: new listening. Not an attempt to understand something that is being said, for, if something were being said, the sounds would be given the shapes of words. Just an attention to the activity of sounds. / (…) And what is the purpose of writing music? One is, of course, not dealing with purposes but dealing with sounds. (…). This [purposeless] play, however, is an affirmation of life—not an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living (…).[12]

Automatisms would operate as standardization and redundancy in the cliché, and would pass through perception, judgment and spatial-temporal syntheses of experience—in the forms of cliché of perception (production of perceptual clichés), cliché of narrativization (from the Aristotelian diegesis to the Hollywood industrial one), and the consequent “entertainment” of the “objective spectator” who, in turn, is an “expected subject,” a type of subjectivity to be produced-and-reflected.

Clichés, clichés everywhere... It is the world of cliché-images, the world conceived as a vast production of the cliché-image. And clichés can be sound or optical: words, visual images. But they can also be interior or exterior. There are no fewer clichés in our heads than on the walls (…). What does that mean? That inside there is the same as outside, namely, clichés and nothing but clichés. And when they are in love it is as if they were telling another in the most stereotyped way in the world the feelings they experience, because the feelings they experience are themselves clichés. The cliché is in us. And our head is full of them, no less than our body.[13]

Images that are legible in advance, with the eyes elided from the trick: the question would be to expose the trick in order to undo the fetish. To discern and expose the grid of visibility, which determines vision, but which in itself is not visible while operating normally. “What else would the word-image or cliché be but the diversion of the eyes towards the unity of the concept to prevent them from becoming accustomed to looking closely at the workmanship, the external debris, the montage, the paste, the clay, the soil of the image, its material mediation?”[14] Automatism as a technology for capturing the living in “culture”—its imaginaries, public opinion, etc.—, against the entropy of bodies—of their desire as seeing and saying—and their coefficient of deviation from all standardization. Thayer points out the dimension of these automatisms as a “gigantic arsenal of imago-powers: painting, photography, cinema, rather than as fine arts, as artifacts of conquest, colonization and neocolonization, of imperial or national avant-garde propaganda, of naturalization and promotion of domination as culture.”[15] The concept of imago-power defines in Thayer the relationship between the production of automatism—standardization of the soul and its “correlative” world—and normative-governmental power: “the image as mise en scène of power, of the image as power, as an artifact of government and regulation of bodies.”[16]

There is no affirmative politics of the image if it is not by dismantling the varied and transversal governability exercised by the gigantic columbarium of cliché and slogan (…). The cliché must be dismantled by elaborating, against the grain of it, a visionary image that allows us to see through the cliché, not only its regime, but the multiplicity that said regime conceals.[17]

And a few pages later, addressing Raúl Ruiz’s poetics of cinema:

(…) Ruiz’s poetics attempts to situate us in the becoming without genesis of what, in many ways, Ruiz finally calls a metamorphic image, not as a passage from one form or metaphor to another and another and another—because in this way one does not leave the synthetic narrative translation—, but as a variation of the quality without transport-of-something, a variation of the quality that is subtracted from the unity, identity and totality of the character, of the action, of the film; sheltered, at the same time, according to another sort of rigors, from a mere mishmash.[18]

Ruiz’s writing of the image would therefore be, against the grain of that of the imago-power, a writing of the metamorphic image as a “variation of quality without transport-of-something”, which would allow “to see through the cliché, not only its regime, but the multiplicity that said regime conceals.”

But why the insistence on the standardization—or total mobilization of the law of value—of perception as an articulation of “intentionality” (correlation of adequacy between perceiving and what is perceived, between wanting and what is wanted, between conceiving and what is conceived, etc.) with a certain diegesis? As we already know, the concept comes from Aristotle’s «Poetics», and we can translate it in a gloss as follows: dihvghsi~ (diegesis) is the way in which the event is narrated more or less unitarily and directedly, around a central conflict. The term is composed by the prepositional prefix dia; (‘through’) and hJgevomai (in Latin ducere, ‘to lead’), referring to a power of shepherding or government—hJgemoniva (hegemony) is, as we know, ‘leading’, and hJgemwn (hegemon), ‘the leader’ or ‘the leading’. But in Greek it refers not only to a power, but also to a knowledge: kavqhgevsi~ (catechesis), to e-ducate, to show the way; ejxhvghsi~ (exegesis), to explain the meaning, to guide seeing/thinking; ejxhghth`~ (exegete), interpreter (of sacred law), counselor, guide or conductor (as docente in Spanish, from Latin ducere); ejxhgevomai (exegéomai), to di-rect, to guide, to govern, to order. So, the function between knowledge and power is drawn here as that of teaching-and-commanding.[19]

If we translate the narrative-industrial principle (narrative determines image) into the language of Aristotelian poetics: narration (dihvghsi~) subsumes the gaze (o[yi~), linking the eye to a spectacle. The diegetic articulation of the gaze passes through narration structured as a unitary and teleological composition, whose action revolves around a central conflict.[20] Such is the structure of the mise en scène: to mount (arrangement or disposition, separate form, formal entelechy) / the scene (metamorphic matter converted into spectacle, a narrativized cliché-vision). The “cultural battles”—whether around the global commodity-form or national-popular aestheticization—make it clear that there is no political and/or religious hegemony without narrative-interpretive hegemony (or “cultural” hegemony as it is called today). Thayer: “To the extent that one can speak of a diegesis of the life of the polis, in each case, the living populations would seem to be aestheticized daily in narrative software.”[21]

Against the grain of the narrative-industrial paradigm, it would be a question of breaking down the intentional apparatus through an “unprepared potentiality” (Averroes), not teleologically organized, of imagination and image (potentiality of imagination versus the facticity of the “imaginaries” that capture it). If it is a question of a writing of the image that allows “to see through the cliché, not only its regime, but the multiplicity that said regime conceals”, then it will be the disarray of the intentional apparatus that leaves in view, at the same time, the regime of the gaze and what escapes of it. To this end, Ruiz will assume the postulate that, in his “writing of the image”, it is the image that determines the narration, at the same time it unworks the pre-given diegesis:

(…) it is the type of image produced what always determines the narrative and not the other way around. This suggests that the image not only fulfils, as it would dominantly do, a metaphorical, illustrative function, representing principles prior to it to a subsequent subject; it suggests that the image would not be reduced to being simply a medium through which a script, a message, a concept, is communicated, subordinating its movement and possibility to it. (…). Ruiz’s image would then defraud the traditional understanding of the image as a means of communication subordinated to a principle, to a prior intentionality. (…) / (…) always, in each case, in an unworking relationship with the pre-given hegemonic diegesis of the case, the device of prejudices or world, the factual a priori already arranged—a kind of genesis of the world, genesis of diegesis, in each case a former a posteriori of the world in its diegesis. But, far from suggesting a menu of possible diegetic games (…), it introduces us, each time, into the unworking of the pre-given diegesis. Hence the political character of its diegesis.[22]

The hegemonic paradigm of industrial narration (narrative determines image) stabilizes the dispositive of intentionality—the “perceptive and narrativized cliché of the soul” to which we have pointed—that is, a certain order of the world as an order of words and things inseminated in the soul as pre-organized perceptive potency.[23] Ruiz, against the grain, not ceasing to narrate, lets the image determine the narration, eroding the narrative intentum itself. If the cliché and theological narrativization “authoritatively frame the multiplicity of the image,”[24] Ruiz’s cinema tries to get that neither the images nor the film stabilize in a representational unity.

(…) before

the code and before the multiplicities, there would be the image, but as

an immanence of multiplicities and code in a differential tension that, now

breathes towards the becoming multiplicities, now suffocates towards the

stabilizing code, always in a back-and-forth motion. The cliché image, the

multiplicity that burdens it, the floating virtuality that over-enhance it,

co-insist in a single immanence that goes from one to the other, shaping the

flows of the image. (…) / The immanence of this double anteriority would then

be the image: at the same time its code, at the same time the sensations

that overflow it; at the same time the plot of the design, at the same

time the complot of multiplicity; at the same time the death mask of

representation, at the same time the fugues without contour; at the same time

the stabilized quality, at the same time the metamorphic variation. (…). Before

anything else there would be the image as co-belonging of multiplicities and

code in differential tension. (…) / Ruiz’s image is not external to the narrative,

it does not subsist outside of narrative dialectics. The cliché, the narrative

articulation, is a necessary condition of the image. It is not, however, a

sufficient condition. The image, according to Ruiz, takes place supplying the

narrative dialectics and exceeding them at the same time, eroding them in that

supply as far as possible. Janic face of the image as power and as

potentiality; as containment and as multiplicity. It is in this destituent

erosion in the midst of the tenacity of the instituted where the affirmative

quality of the Ruician image resides. It is because of this affirmative

potentiality of the image that unworks the cliché that Ruician poetics of the

image is also a politics; a poetics-politics.[25]

Here

there is a key: the “image” is always before the “dispersive material

multiplicities” and the “codes” that unify and contain them, as a differential

tension between them—and not as a mold, model or formal entelechy

that is only read as a dematerialized and authorizing code. In this sense,

Thayer emphasizes that this cleavage can be understood as a differential

between body and technique, or, put another way, between body and

culture: such a differential will constitute the styleme or exote

image—what Ruiz

said allowed “living inside and outside of culture [grammar, logic, cliché]

simultaneously, integrating and not integrating.”[26] Thayer points this out in relation to the

more “folkloric” aspect of Ruiz’s films:

And in «Imagen exote»:

Instead of being in a world and seeing through the world that arrays the eyes with which he/she sees, the exote becomes that which is worldless, which, without the eyes of the world, palpates, gropes between worlds, in a twilight, a fade, a continuum of transformations in which the passages do not establish borders. (…) / (…) these films propose singularizing images, a testification of the popular much more as an exote than as a utopia of the identitarian national and popular.[28]

My hypothesis for reading Thayer as a reader of Ruiz is that, in addition to bringing into play a concept of a metamorphic image (variation of quality without translation-transport), Ruiz brings into play in his poetics a multiplication of perspectives that seeks to destabilize the intentional apparatus until the place-without-place of all of them appears, a certain profane illumination that has nothing to do with the assumption of a theological meta-reader.

Metamorphic potentiality does not germinate if it does not permanently experience in its performance the rigors and inertia of the narrative diegesis that surrounds it everywhere. The potentiality of the metamorphic image does not take place if it is not eroding, in media res, the propagation of the narrative image that permanently besieges it. (…) / The produced image that determines the narration obeying figural rigors, so to speak, non-compositive, non-argumentative, non-causal, on the brink of experience, destabilizing in each plane its unity in qualitative variation. Each fragment of the puzzle or film will demand, in its dictation, to be inscribed in other—indefinite—compossible and incompossible puzzles between them, multiplying each puzzle and the referential film from each plane, raising in each image virtual films in parallel, as if each plane of a film of five hundred planes were converted into a main film, and the main one exploded into five hundred films.[29]

THE PLAY AND THE QUESTION ON EXPERIMENTALITY

We are now in a better condition to answer the question: How does the performance Forgotten Science relate epistemologically to this set of ontological problems concerning art and politics? In my view, it does it putting at play the technology of singularity and interruption of organic theater. How did we play such an interruption? First of all, regarding the problem of the pit: although we attempt to abolish the representational distance between performers and the performed (eliminating the classic separation and subordination of praxis to theory, and conceiving of theory in a performative and defective way),[30] with regard to the pit between stage and audience, things are a little more complicated: we are not trying to assault the audience by transmitting some instructive or edifying message, winning them over for some “cultural battle” (the work, in my view, has no pedagogical or pastoral intention, but rather seeks to destabilize the perceptual apparatus); nor do we invite the audience to assault the stage, in the sense that they might leap over the pit and occupy the stage to be invested with the spectacular brilliance of it (now everyone could be a “star” in that luminous, magically doubled world). None of that. The first abolition of the pit (the interruption of representational distance) determines that the stage is not a glowing, glorious, harmonious, and coherent representational space, but an opaque one, subject to accidentality, conflict, and ambiguity, where the event always exceeds my subjectivity and its glares with things and events, and with itself. That is to say, the abolition of the representational principle determines that the stage is a place of chiaroscuro and indeterminacy, just as life outside of it is, and just as the life of the members of the audience is as well. Then, on the one hand, following a Benjamin’s formula, we interrupted the operation of the bourgeois conception of language as a “means of communication” of fetishized meanings—by analogy to the trade of commodities—,[31] so that we tried to recover a communicability of language which would involve assuming that experience in its singularity resists its fixation in the ideal element of language and its categorial and spatio-temporal schematisms. For the same reason, we avoided the subordination of the action under a plot-and-director dispositive—the narrative woven from clear and distinct propositions, as well as diegetics in its classic Aristotelian structure. The absence of the centering-sovereign figure of “director”[32] was essential: for this performance we rehearsed practicing responsiveness in the absence of a central command, so that instead of coordinating behind the direction of a predetermined script (focused on the director’s organizing intelligence of the meta-narrative), what we did was exploring other ways of articulating our responsiveness as a group, following the anarchical and sympoietic figures of queerness and entanglement.

Regarding the diegesis, what we did was displace the causal-linear narrative, and rather to play with a kind of narrative collage. Each of our actions or subtractions plays with the others, like a sounding board, and something is generated that is greater than the sum of its parts (but that “something” emerges as a momentary effect, not as a cause). At first, you can’t see anything, but the results can be very interesting. During the rehearsal days, we talked about the “plan” that didn’t exist, or that in any case was an emergent property (the “emergent plan,” we called it). We told each other that, in between our daily businesses and daydreams, we had been imagining things for the performance. “The other day—I wrote on our chat—you were talking about nature and technique, technology and forms of relationship (symbiosis, devastation, etc.). For that, the sound section could offer field recordings processed by Sasha, which cover a spectrum from the everyday to the unfamiliar, in the sound of lab elements. With the MIDI controller, Sasha can deploy the sound clusters with great dynamics. In my case, I have some sections of electronic sounds (with a synthesizer connected to the circuit of knives, oranges, and my body), mixed with field recordings of flickering light bulbs and night singing crickets that I drew from an online sound library, and also the looped sound I recorded with my mobile phone of a jet of water from a sprinkler hitting the metal light post in front of the studio entrance. I am going to generate a more corrosive noise too, for a more devastating noise section, since the previous section is rather pleasant for electricity lovers. And finally, the plant’s sonification system is ready. Sasha, as a sound section, we can perform separately or together. The plant system might interact with Jae or with any of you who imagine or come up with something with it. I’m also imagining a bassline with the plant system in a mode where the synthesizer, in its translation, highlights more the electrical flow of the plant’s metabolism, which is more constant and mantric, achieving a more ambient feel with the addition of the basslines of the bass guitar. All this is emergent, so it will connect and mutate with your gestures.”

The piece also refers to the relation between identity and difference, through the question of replication, metamorphosis, and translation of subjects, things, and events. It is a simple and fundamental hypothesis: nothing and no one coincides with themselves. In the piece, this takes place in the changeability of roles both among performers (the entomologist who sings and dances, the dancer who makes music, the philosopher sonifying a plant through electronic transducers, the physicist who plays noise and clusters of field recordings, etc.) and among characters (in the dimension of the illusion of action: characters whose roles are not clearly discernible, whether they are scientists who become artists or vice versa, etc.). The piece radically derails the centrality of the person (my subjectivity, my identity, etc.) and its social function (my discipline, my work, etc.): everything is triggered in the dimension of relationality, its encounters and deviations. In the dimension of identification and function, the piece rather introduces decentering and disidentification, displacement and dislocation. In this sense,[33] despite the fact that at times there seemed to be a certain disconnection between the elements in play, “as if they were navigating through different channels,” a significant part of the performance’s opacity has to do with this interplay of connection/disconnection: as in “real communication” in everyday life, there is no absolute connection and harmony (the ideal of successful and functional communication which often coincides with a religious or functionalist idea of the social “bond”), but rather ambiguity, blind spots, conflicts, and communication difficulties. A good example of the exploration of this coefficient of (dis)connection is the collaboration between John Cage’s music and Merce Cunningham’s dance.[34] Other times, connection and responsiveness occur through hidden channels, as is the case with Chatziparaschis’s character, who sometimes seems disconnected because he is focused on his laptop screen, while he is actually connected and responding, translating himself through the eyes of his robot, which he mathematically calibrates on his computer to adjust to variations in the performers’ distances in space and the lighting conditions in the room. An interesting observation concerns the low lighting in the room (a powerful archaic element of opacity) and the “multiple activities competing for attention,” all of which produced an “initial confusion” that was not equivalent to “lack of clarity” (“I took this to be intentional, meaning audience members had to decide for ourselves where to focus”). The piece, in effect, plays like a constellation of (dis)connected elements: people dancing, singing, and playing instruments (artists?); people working on computers and offering scientific explanations as if in a David Lynch dream (scientists?); people manipulating electrical circuits to produce layers of noise with distinct electrical textures (what kind of activity is that?); people interacting with a sonically expressing plant (dancing with it, studying it, etc.). There are layers of acoustic sound (singing, voices and short speeches, leather drum, steel drum, sounds from the audience and the street, a baby called Lucian Amaru suddenly crying), electroacoustic sound (bass guitar), electronic sound (plant sounds and the circuit of conductive objects translated by synthesizer), field recordings (clusters of lab noises organized by a software); in the dance, relationships are done and undone, “different solos, duets, trios, quartets, and the mutations between them that blend into each other.” Finally, an important key regarding the question of identity and difference: there is a moment when, in the middle of a passage describing experiments involving observing electrical signals between humans and plants, the character performed by Maccaro says the magic word “replication,” referring to the idea of experimentation as repetition and reproducibility in the modern scientific method. The idea here is Deleuzian: repetition implies difference, miracle. And then the performers begin reproducing the movements they had done so far and change roles, unraveling the subject-object relation and the tautological idea of repetition.

Dance, music, multiple sonic and bio-sonic layers, and the space of the robot’s visual projections constitute the metamorphic medium in which the responsiveness and translation between humans, a plant, machines and audience are played out. Regarding “the plant,” it is an important icon in the symbolic constellation of the piece. It appears in the handmade poster I made for the piece—a linocut engraving, in black and in red—which refers to the geminate life of the plant, oriented both towards the sky and the center of the Earth (heliotropism and geocentrism), and also to the human violence against Earth (exploited, devastated), of which technoscience allied to the power of capital is a part. Of course, beyond the human, it also refers to a dark ecology (involving non-human agency, beyond the human and its representational and operative sovereignty and enclosure). Not an animal, but a plant is the one interacting in this case with humans and machines. The plant, traditionally considered an inert ornament on the stage of the human-animal drama, indifferent to its environment and lost in a chemical dream, detached from any life of relationship, appears in the piece acting, expressing its own sensitivity, responsiveness and agency. To achieve this, I have “sonified” the plant by performing two translations: using an electronic transducer and electrodes, I have translated the plant’s electrical signals (its elemental metabolism and its responsiveness to the environment) into computer data, and then, using a MIDI controller, I have translated this computer data into synthesizer assigned sound. The result is that one can perceive the plant’s life and responsiveness through the sound of the regular electrical flow of its metabolism, as well as its responses in interaction with surrounding animals (through touch contact and, before and after that, in its perception and response to the electromagnetic field of our bodies and those of other animals around) and as a reaction to other environmental factors (ambient light, temperature and humidity levels, stress, receiving water, etc.). Through the electronic transducer (as a mechanical mediation), the plant can interact with humans, it can “dance” with them, and respond to their approaches and requests. In some ways, the system operates similarly to a theremin… except that the plant’s responses are not mechanical, but varied in timing, manner, and intensity, like those of all life forms. The plant, through machine mediation, interacts with human animals, and plants and humans interact with other machines—like the circuit of electrically conductive objects to produce noise with electricity coursing between my body, knives, and Riverside oranges; or like Chatziparaschis’s mathematically calibrated, real-time robot eyes, staring at us from the sides of the studio while, in the act, such a robotic vision is visually projected back onto us, with all those light beams being responded to, in addition, by the plant.

In that direction, it seems to me that Forgotten Science experiments playing a game between concealment and unconcealment, and responsiveness at the existential level. In this sense, it seems to me that Forgotten Science experiments in a play between concealment and unconcealment, and responsiveness at the existential level, in the midst of a queer entanglement. This play, for example, with respect to science, can make visible the scientific habits of the subjects of actually existing science (critique of our scientific ideologies and violences through the expression of involuntary memories), and, at the same time, show forms of relationship and knowledge that, while they already always occur in everyday life (virtuality of popular imagination that escapes from power dispositives, unexpected compositions of bodies and ideas), we leave them aside because they do not coincide with the idea of normal science and normal society. For that reason, and regarding the title of the piece, I think the “forgotten” science as one that “does not yet exist”: the counterintuitive formula is because what is forgotten is already there, concealed in the very relationality of existence. “Forgotten Science” is not that which once was, but one which is not yet: as the emergent event is always to come, it doesn't stop to arrive and has to do with the openness of imagination and affects, experience becoming experimentality, both in arts and sciences. The bureaucratic tendencies inside the university institution tends to forget the science that does not yet exist, in order to administer, reproduce and innovate in that which already exists. We assume that the science that does not yet exist is not just that of the innovations of present-day science (the innovations to come, but relying on the same logics and affects), but rather some kind of “strange or foreign” (strannyye, in Russian it simultaneously means “queer” and “strange”) science, a science that thinks differently, an unfamiliar science that remembers or pays attention to things that are imperceptible and forgotten for the science of today. It resonates with Salon’s discussions about queerness, entanglements, symbiosis and sympoiesis, khôratic spaces (climate, language, love, etc.), Gaïa and Gaya hypotheses (complexity-relational oriented and “gay science”), the relationship between mathematics and the untractability of matter, the measurable and the immeasurable, the attention to the (more or less uncontrollable) metaphoric nature of scientific language, experimental art and “intentionality”, the originary technicality of life and the becoming dispositive and war-machine of late modern technocapitalism, etc. A new idea of non-Cartesian science relying on queer entanglements?

In any case, Forgotten Science would propose a postfoundational form of “critique” understood as reflexive indocility and expressiveness, instead of the naive and/or comfortable ideological normalization, overprotection of one’s own subjectivity, obedience to and mimesis of normal (normalized) forms of subjectivity and sociality. The way of addressing the question of the “pit” would also imply a political positioning of non-alignment within the current war regime, that is, a position neither hegemonic nor anti-hegemonic, but post-hegemonic—the question of “positioning,” again… although the political right wing is always the party of the established order (while the “left” means interruption of that order, transformative popular imagination and performance), the question here would not be taking an “extreme left position”, but rather placing oneself to the left of any position (Thayer).

Finally, some reflections on “experimentality” both in the sciences and arts. Let me present three little scenes.

The first scene corresponds to the Ancient Greek definition of experience as “ecstasy.” Erin Graff Zivin[36] offers us a concept of exposure that can give us a clue to begin here: exposure, from the Latin exponere, “set forth, lay open.” It is a concept that allows us to think of a figure of the subject’s opening that goes against the grain of that of the “sovereign subject, to whom, according to Derrida, nothing ever happens.” It is a movement of departure, from the proper and familiar to the other, to the strange and unfamiliar. In the ancient Greek figure of ecstasy, the soul appears precisely as exposure, and the world as an excess (to put it in the style of the intentional analysis of phenomenology). Experience always exceeds experience, and what it discloses never fails to arrive—whether corresponding the sense of our projections, or on the contrary, as a countersense (a fire or an earthquake, or a war, etc.).

The second scene corresponds

to a medieval concept of “experimentation”. Let us consider the concept of

“potency” established in the Western philosophical and theological tradition:

in the process of becoming, potency precedes the act in the subject that is

brought from potency to act (in this sense, potency is understood as a praeparatio

or preparation inherent in the subject of change). Contrary to this

definition of a teleologically captured potency (that is, the potentia

in the narrow sense that we have just mentioned), in Averroes we find a radical

and anarchic idea of potentiality (what Averroes calls the possibilitas),

a possibility that is expressed in the aneconomic effects of experience,

thought and translation (effects that are not susceptible to transcendental

control by the subject). This radical possibility is also expressed in as a

potentiality of interrupting, deactivating, disarticulating, deposing,

destituting or even derailing the archaeo-teleological machine, in order to

open for other common and experimental uses of the imaginative flesh and the

life of relation, that is, for profane uses beyond the consecrated ones. Potentia

would work already inseminated as a formal a priori in the soul, while possibilitas

would have to do with exposure, relationality and interruptibility, a radical

potentiality not captured by intentionality—whose concept has become a

dispositive for sovereign-pastoral power in its Aristotelian-Thomistic drift.

The “material intellect” as a common and anarchic potentiality occurs in a

space that is not reduced to a “geometrically objective space” or a

“psychologically subjective” one, but is played out in a “relation of free and

common use,” an “aneconomic place irreducible to any possible economy,” since

it exceeds, in its possibility, both the phantasmatic ground of the “original”

representationally fetishized and anthropologically inseminated, as well as the

archaeoteleology of means-ends and their specific technical behaviors.

The third scene: the detour from experimental science to experimental art and politics. In Averroism we find an experimental concept of intentionality (that is, the soul as exposure, the world as excess). However, its drift in the late Middle Ages intersects with the transformations of modern epistemology; I am mainly thinking of the transition from the demonstrative science of Aristotle to the experimental or inductive science of Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum. Instead of demonstrating the world without recourse to sensible experience, but only doing it from the attributes contained in the idea of God, it was now a matter of opening up from the reflective closure of the mathematical cogito to experimentation with phenomena that we find in the openness of the natural world, in that field of perception that apart from being vast, never stops to arrive. But this experimental nature of science was quickly marked by the development of modern science as a humanistic and anthropocentric horizon of power and predictive control over nature (“knowledge is power”, says Bacon). It is against the grain of this modern epistemic-political horizon that, after the war catastrophes of the 20th century, art emerges in its “experimental” aspect: just as David Lynch said that there had to be room for wandering beyond the Aristotelian control of narrative, so we can also say that the expressiveness of experimental art suggests, in line with Benjamin’s idea of the “death of intention”, that the world cannot be reduced to a home, nor psychic life to a subjectivity. Connecting with Korotneva’s concerns about the measurable and the immeasurable—and analogizing the methods of experimental sciences and experimental arts—, Maccaro said that, viewed from the perspective of the modern scientific method, perhaps while science was the research of the knowable, art would rather be a search of the unknowable, that which escapes and cannot be controlled in the categories and fixed in the tongue of modern science.

That is why it seems to

me that Forgotten Science is a performance in which the spectator who is installed in the comfortable

habit of the narrative-industrial diegesis “does not find the subject”

and “does not see where it is all going,” sometimes even “missing what

is happening.” The intentional structures of recognition and empathy are

broken—and a “dimension of strangeness” or “enigmatic corpus” breaks in, and

one experiences a “constellation of signs that conspires against plain

reading.”[37]

[1] Susan Leigh Foster, “Dance Theory?”, in Judith Chazin-Bennahum

(ed.), «Teaching Dance

Studies», Routledge, New

York and London, 12005, p.

31.

[2] Ann Ronell, “Willow Weep for Me”, World Artists, United States,

1932.

[3] Within and beyond our performative cell, in addition to each of the

performers of the piece, I thank Jorge P. Yánez, Cinthia Durán, Marielys

Burgos, and Mallory Peterson for the chance to think about dance and

performance through dance and performance. To Jorge, especially, for the

creative struggles around the ethics and politics of the method at play (the

“green star” and the “eclipse”).

[4] For example, Sarah Kember & Joanna Zylinska,

«Life after New Media. Mediation as a Vital Process», MIT Press, Cambridge, 2014; although Kember and Zylinska turn to

the etymological relation between theater and theory, not so much to consider

how theater and theory install a “pit” (which later will be translated into the

modern subject-object separation-correlation), but to argue that theory and

theater are analogous (theory as theater, theater as theory), given that both

are performative and can operate within different medialities. “We are making a

claim —write Kember and Zylinska—for the status of theory as theater (…), or for the performativity

of all theory—in media, arts and sciences; in written and

spoken forms. We are also highlighting the ongoing possibilities of

re-mediation across all media and all forms of communication. From this

perspective, theater does not take place—and never did—only ‘at the theater’,

just as literature was never confined just to the book, or the pursuit of

knowledge to the academy. What is particularly intriguing for us at the current

media conjuncture is the ever-increasing possibility for the arts and sciences

to perform each other, more often than not in different media contexts”. But the problem of the “pit” remains unaddressed in this approach to

the medial translatability of arts and sciences.

[5] Leigh Foster, opus cit., pp. 19-34.

[6] “Seems like dance studies is often repressed within the academy. /

Yes, well, dance as an activity or as a subject in any form had a very rough

time getting accepted into the university. I remember as an under graduate

going to the provost of my college and requesting credit for a dance class. He

responded, ‘Dance is a noncognitive activity, and has no place in the

university curriculum.’ / I’ve never experienced that kind of attitude, but

it’s true that dance is always sneaking in through the back door of physical

education or theater arts, or sometimes music. Dance teachers manage to argue

for its validity based on the idea that dancing offers a unique way of knowing

the world—which is really a wonderful proposition. / (…) I think what’s

interesting about those kinds of statements [‘dance is

a noncognitive activity’, and similar] is the organic

relationship they presume between dance and other fields of inquiry. Instead of

imagining that every kind of inquiry cultivates the mind, the heart, the body,

and the spirit, they partition the person into symbolic segments, such as mind,

heart, or body” (Leigh Foster, opus cit., pp. 24-25).

[7] Ibidem, pp. 22-23.

[8] The theater (qevatron) metaphor refers to a voyeuristic

doubling, reflection (distancing itself from itself and turning back on itself)

and repetition (from the “action” to the “spectacle” as its representational

repetition, as the aestheticized double of the event). The theater thus inaugurates

the spectacle with an exhibition value, distinct from the ritual

(immanent cult without distance from itself; in ritual there is no spectacle or

spectator, no point of view, no distance, no discernment—that is, no

“critique”—, but only faithful, initiated, devoted, belonging, and obedient

individuals). In theater, the spectacle takes reflexive distance from

the action; in the ritual, there is pure action without spectacle or

reflexive distance. The theater pit marks the critical distance and the

“autonomy” of the spheres of the stage (action, life, actors) and the audience

(spectacle, reflection, spectators: representation of the event, event as

representation). Contrary to this idea of autonomy of spheres as a

condition of critical distance, the dynamics of the abolition of distance

appear in the splintered figure of invasion: the “totalitarian assault

by the stalls on the stage” (monumental revolutionary avant-garde, revolution

of the “People” against the old scene of the dominators, with a bloc of

leadership and reproduction of the sovereign form), and the “totalitarian assault

by the stage on the stalls” (conservative avant-garde, total mobilization of

fascism, aestheticization in a ritual in which the masses merge with the

sovereign, expanding the scene as a total spectacle and choreography). In

short, the imposition of a universal from the audience (vanguardism) or from

the scene (fascism); see Willy Thayer, «Technologies of Critique», translated from Spanish into English by

John Kraniauskas, Fordham University Press, New York, 12020, p. 49

ff.

[9] Ibidem, p. 10 ff.

[10] Cf. Walter Benjamin, «Sobre el

lenguaje en general y sobre el lenguaje de los humanos», in “Iluminaciones IV. Para una crítica de la

violencia y otros ensayos”, translated from German into Spanish by Roberto

Blatt, Ediciones Taurus, Madrid, 21998, pp. 59-74.

[11] Willy Thayer, “Raúl

Ruiz. Imagen estilema”, in Revista Otro Siglo, vol. 1, nº2 (2017), p. 5.

[12]

John Cage, “Experimental music”, in «Silence

(50th Anniversary Edition)», Wesleyan University Press,

Middletown, 102013, pp. 10 and 12.

[13]

Gilles Deleuze, «Cine 1. Bergson y las imágenes», translated from French

into Spanish by Sebastián Puente and Pablo Ires, Editorial Cactus, Buenos

Aires, 12009, pp. 489-490. Thayer, for his part, speaks of “highly

incorporated clichés by virtue of which we know and recognize the everyday

life, clichés in which we redound; clichés that exist before us, that speak

through us, and that will continue to exist after us” (Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen estilema”, p. 7).

[14] Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen estilema”, p. 6.

[15] Ibidem, p. 7.

[16] Ibidem.

[17] Ibidem, p. 6.

[18] Ibidem, p. 27.

[19] Thayer quotes Ruiz, apropos of the

pastoral notions of hegemony and institution, unity and teleology

(Providence) around a central conflict (civitas Dei versus civitas diaboli),

illustrated in the ecclesiastical dispositive: “The Church ‘constitutes the

institution par excellence. To speak of the Church (...) is to speak of

bureaucracy and dogmatism (...), not only for the simple fact that every

decision depends on another (...) in perpetual ongoing, but also because (...)

the untouchable dogmas by definition (...) engender that appearance of

democracy that constitutes the permanent debate of ‘interpretation’ (...); the

Church is, then, the totalitarian system par excellence, since it is not based

on police violence, but on the free acceptance of its members (empathy). The

Church is, perhaps, the most accomplished expression of the ‘fascination with

totalitarianism’, which explains its two ‘sources of pleasure’: (...)

discipline, (...) power’ (Ruiz). Its mission was to ‘transform the world (...)

and to the extent that it achieved this, we are no longer even aware that its

effect is absolute. It has been assimilated (...), I was very impressed when I

read Gramsci for the first time and discovered that he compared the Party to

the Church, and recommended the Jesuit model as an example to follow. And then

there are naturally all the American theories of institutions. But what none of

these theories express, and which from my point of view is an essential element

in all institutional behavior, is the symptomatic bad faith produced by the

fascination with the perfection of the institution itself, apart from any

interest in the deep reasons for its existence’ (Ruiz), reasons that the Church

administers on the deep surface of its earthly estate” (Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen

estilema”, pp. 17-18).

[20]

Ruiz: “There are always conflicts. The problem is when a conflict hegemonizes

other conflicts and makes disappear the extremely rich image—the tensions of an

image—by centralizing these conflicts in one” (quoted by Thayer in «Imagen

exote», Editorial Palinodia, Santiago de Chile, 12019 p. 68).

This is what happens when the discourse of bellicose nationalism erases the

class struggle on the “internal front”, or when the discourse of geopolitics

overcodes and makes local conflicts disappear.

[21] Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen estilema”,

p. 11.

[22]

Ibidem, pp. 14 and 17.

[23]

Thayer: “In this direction, Ruiz’s poetics of cinema, much more than a

treatise on film practice, constitutes a set of writings that, from its

diversity of supports, attempts to disarray the Western understanding of the

image as representation, as an expanded and dominant narrative diegesis”

(ibidem, p. 21).

[24]

Ibidem, p. 19.

[25]

Ibidem, p. 20.

[26] Ibidem, p. 6.

[27]

Ibidem, pp. 41-43.

[28]

Willy Thayer, «Imagen exote», Editorial Palinodia, Santiago de Chile, 12019,

pp. 11 and 17.

[29]

Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen estilema”,

p. 27; see also Thayer, «Imagen exote», p. 16 ff.

[30]

Jacques Lezra, «On the Nature of Marx’s

Things. Translation as Necrophilology», Fordham University Press, New York,

12018.

[31] Although, in addition to the capitalized language of commerce as a

master analogy, one can also point to the fetishization of the languages of

dance and music, as Leigh Foster does: “Condillac thought that language was

preceded by a kind of primitive song/dance. When people were afraid, or

excited, or in need, they would spontaneously gesture and cry out. He contends

that eventually people realized that these gestures were very helpful in

signaling, say, the approach of a wild animal, so that everyone would know it

was coming, and, even though they hadn’t seen it themselves, they could see the

gesture of the one who had and therefore protect themselves. Both speech and

dance, he argues, grew out of this protolanguage. / So, it’s natural to

gesture/cry spontaneously in response to danger. And then speech grows out of

this primal responsiveness, as the thing that it is not. That makes speech

logical and contractual. (…) Condillac is perhaps the first philosopher to

think about language in relation to the body this way. But what’s also

interesting about him is that he spent a fair amount of time discussing how

dance, like speech, evolved into a standardized set of conventional signs that

people use to express themselves. Like language, dance developed into a

contractual system of signification”; “So, where does music fit into that

model, and what about music theory? That’s a wonderful question. I never

thought about music theory in relation to the kinds of cultural and critical

theories we’ve been discussing. Why not? Well, music theory is the study of a

given composition’s harmonic and rhythmic structure. It examines the underlying

principles of the scale, melody, and tonal progression and the structures of

meter and tempo that are generating the composition. And it looks at forms the

composition as a whole can take, such as a sonata or a fugue. So, the

equivalent in dance would look at the basic vocabulary of a given piece, how

the moves are related to one another, and then also how they are sequenced. And

then also how a given composition develops through the use of theme and

variation, or ABA, or story line. That’s where the analogy breaks down. Music

theory has focused exclusively on the internal structure of a given work with

little or no reference to what it might mean or how it might signify something

in the world. In fact, only recently have scholars who call themselves

musicologists begun to forge connections between musical structure and

structures of feeling, or even gender, and narrative. (…). I suppose you could

have a theory that the meaning of a dance was complete within its use of

variation, rhythmic phrasing, repetition, and reiteration, etc. But the body

always signifies so much more than that kind of formalist analysis would allow”

(Leigh Foster, opus cit., pp. 30, 25-26).

[32] The general orientation of the creative process involved, of

course, the specific orientation of different aspects according to each

individual’s disciplinary background: although throughout the piece the

performers interchange roles (between dancers, musicians, and operators of

bio/sonic machines and robotic visual organ projections), Yánez guided the

expressive openness and choreographies of the non-professional dancers, just as

the bio-sonic, field recording, and musical sections were supervised by Korotneva

and Díaz-Letelier, the singing section and surreal scientific scenes were led

by Maccaro, and the real-time mathematically operated robotic organ section by

Chatziparaschis. As a piece of integrated arts and technologies, none of them

has an exceptional or predominant role over the others (the music is not

subordinated to the dance, nor the machines to the music, etc.).

[33] I am grateful here for the valuable comments and suggestions to us

by André Carrington (UCR Department of English / Speculative Fiction and

Science Cultures), Sage Ni’Ja Whitson (UCR Department of Black Study), and

Jacques Lezra (UCR Department of Hispanic Studies), who attended the

presentation on June 4, 2025.

[34] Merce Cunningham Dance Company & John Cage, “Beach Birds for

Camera” (New York, 1993).

[35] Thayer, “Raúl Ruiz. Imagen estilema”,

p. 6. In this regard, Leigh

Foster writes: “Well, the problem with the theory

that dance reflects culture is that it makes dance a kind of passive byproduct

or imprint of other more dominant cultural forces. But couldn’t you also think

about dance as producing culture, as generating cultural values through the

ways in which it cultivates the body and brings people together?” (Leigh

Foster, opus cit., p. 22).

[36] Erin Graff Zivin, “Exposure”, en Political Concepts: A Critical

Lexicon, April 29, 2024, link:

https://www.politicalconcepts.org/exposure-erin-graff-zivin/

[37] Thayer, «Imagen exote», p. 55.